June is the month when the NPS commemorates the 1969 Stonewall Uprising and celebrates LGBTQ+ people and their histories.

Why do we use the word “queer” when talking about LGBTQ+ people? It’s an important question,

The acronym LGBTQ+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and “+” for other identities not covered by the other letters) is best used when describing a community of people. When you know how someone identifies, please use that term! In recent years, the term “queer” has risen in popularity as an umbrella term to address individuals in the LGBTQ+ community. Especially when talking about people in history, using “queer” is great to encompass those who fell outside of the standards of society. There are a lot of terms used in queer spaces and when talking about queer history that may be unfamiliar, and that’s okay. Ask questions and seek out resources like this dictionary.com article on LGBTQ Terms to help better understand the words being used.

What does queer history have to do with Death Valley?

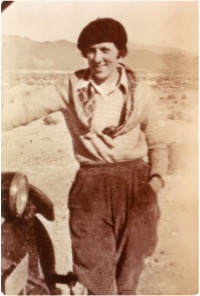

DEVA 53606, Death Valley National Park.

Everything! Queer people have played roles in every aspect of human history, whether we know it or not. In Death Valley’s case, we are lucky enough to have a clear example of a queer woman who lived and worked in Death Valley—Louise Grantham.

Louise Grantham was born in Ohio in 1900 but moved out to Los Angeles as a young woman to attend University of Southern California. Her father had been investing in a prospector for years without any money in return. Granthan decided to seek out the prospector near Death Valley.

When she arrived, she discovered the miner was broke and had no promising claims. Still, Grantham’s trip to Death Valley was the hook she needed to begin her mining career.

Louise Grantham spent a few years traveling to Death Valley on the weekends to prospect, and eventually took up residence in Warm Springs Canyon by the 1930s. The current buildings and equipment located at Warm Springs Camp were later built by Louise Grantham and she regularly stayed there with her “close female friends” that she drove out from Hollywood every other week or so. “Close female friends” is in quotations because some of the women she stayed with are suspected to be her girlfriend at one time or another.

Grantham had several relationships with other “independent” women where they lived together and never married, even sharing bank accounts with long-time “close friends.” There are a few people who knew Grantham during her lifetime who have confirmed she dated women. There is also a rather infamous quote from an early prospecting partner Frank Brock who tried to sleep with Louise Grantham only for her to tell him off and remind him, “Also, I don’t like men.”

One of the women she lived with for over 30 years was Dot Ketchin. After decades of living at Warm Springs together, Dot Ketchin stands to the left of Louise Grantham in the photo below. Louise is the third from the right and Dot is fourth from the right.

Just because we celebrate queer figures in our history does not mean we can’t be critical of them as well. Louise Grantham may have been a well-respected mine owner and LA socialite, but her ruthless business attitude spawned a multi-decade dispute that ended with the removal of water rights from Robert “Bob” Thompson, a Timbisha Shoshone man whose family had lived in Warm Springs Canyon and relied on the Warm Springs there for agriculture for their whole lives.

In the 1940s, Grantham originally paid to access Thompson’s water for $10 a month. After prepaying 6 months, she called Thompson’s claim to the land into question and refused to pay him any more money.

Thompson took his claim to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Death Valley National Monument got involved as well. Grantham dodged court summons for years and leaned heavily on her early mining claims, eventually wearing Thompson, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the National Park Service down until she finally got legal claim to the land in United States v. Grantham et. al. It is a very complicated case, as most water rights cases are, but

the main takeaway is that her mining claims eventually became some of the most successful talc mines in the West on the basis of a water source long tended to and relied on by the Thompson family.

All of this is to say that queer history, like all history, is complicated.

A few good resources for more on LGBTQ+ History:

LGBTQ Heritage Theme Study – Telling All Americans’ Stories (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

International approaches to LGBTQ public history | National Council on Public History (ncph.org) Stream L.A.: A Queer History Seasons & Full Episodes | KCET